…then you started seeing shows like “China Smith” and “Dragnet” and “Perry Mason.” It had dark crime, pinged themes…

Alan K. Rode has deep roots in Hollywood. His family has been working in and around the movie industry since the 1920s. He is the author of two fantastic biographies: Charles McGraw: Biography of a Film Noir Tough Guy is a critically acclaimed examination of this steel-jawed gravel voices actor’s life. Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film is the first all-embracing biography of the director of Captain Blood (1935), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Casablanca (1942), Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), Mildred Pierce (1945), White Christmas (1954) among others.

Alan has been the producer and host of the annual Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival in Palm Springs, California since 2008. He is a co-founder of the Film Noir Foundation. He has produced numerous featurettes to accompany classic film releases. He is also the chairman & programmer of the historic Hollywood Legion Theater.

Alan K. Rode Interview Transcript

Today I’m here with Alan K. Rode, historian, author of two very interesting books, film preservationist, and Film Noir aficionado. How are you doing today, sir?

Oh, if I was having any more fun, I wouldn’t know what to do. Thanks for having me on John.

I’m very excited to have you the information that you provided to Helen Garber for our class was just spot on. Perfect. And I’ve been wanting to talk to you since then and I know my audience is going to get a lot out of what you have to say.

Well, Helen is an old friend and I’ve known her for many years and she and her husband used to come out to my film festival in Palm Springs, which unfortunately because of the Corona virus, excuse me, I had to postpone from the second week of May and now I’ve rescheduled it from the December 3rd to the 6th. And that’s the Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival. Our 21st year. And that’ll be at the Palm Springs Cultural Center in Palm Springs on December 3rd through the 6th. But Helen’s an old and dear friend and I was, I was certainly glad to help her out with providing her with some film titles for class.

No, if everything goes right, I guess she’s going to teach it again next year or the advanced class.

Great. Yeah, absolutely.

Well, Alan, could you give us a little bit of your background and hit what you see as the high points? There’s so much. I’ve been reading your bio’s and stuff and I could go on for 20 minutes or so, but what do you think the high points that everybody needs to know?

High points about me? Well good grief. Well I was born in I was born in New Jersey outside New York City in the 1950s and I, I was, grew up in New Jersey and I grew up in a how to say a film centric family. My, my mother’s but my mother’s side of the family was kind of like it’s kind of like the road company of You Can’t Take It With You (1938). All these character’s her stepfather. My grandfather was a composer musician who came to the United States in 1922 named Alfonso Corelli and went to Hollywood in the twenties and sold prohibition whiskey out of his violin case, and worked as a composer at Universal Studios and a bit actor and played mood music on silent film sets and so forth. My grandmother was married to a cattle rancher, had her radio show, had a radio show in Hollywood.

And so, my mother was born in Hollywood in 1922 and was an extra in “Our Gang.” So, I really grew up steeped in the milieu of the movies and Hollywood and friends of theirs and the business. And both my brother and I, my older brother and I, and incessantly watch movies on television and catalog the movies and who was in them and so on, so forth. And so, I took a rather circuitous path to writing about all this stuff. I ended up getting my draft notice going into the Navy, leaving New Jersey. I left New Jersey in like the early 1970s after I graduated from high school. Spent a lot of time on the West Coast in San Diego, forged a career in the Navy, aerospace after the Navy. I was a general manager, traveled all over the world, did a lot of different things, but got married, had a family.

And then towards the end of my time in the Navy and so forth, I started writing about film. I had always been a writer both from a business sense and for my own edification. And then I moved up to Los Angeles and I think 2001. And someone threw some money at me for a job. So you know, I, I let them set the hook, came up to Los Angeles and got much more involved and got involved with Film Noir, which I always was passionate about and was in the ground floor of the forming of the Film Noir Foundation and started hosting movies. And I wrote, my first book I think was published in 06 or 07. It seems a long time ago about Charles McGraw, which was a real serendipitous exercise because I got to know his family, his widow, his friends.

And as I got to know more about this, I said this, but this was a story that should be told. So, I wrote that book and then I followed that with this Magnum Opus for lack of a better term on Michael Curtiz which took me a long time to ride and took me to Europe and all over the place. I have, I’ve had my own film festival in Palm Springs for 21 years and doing a lot of different things. Thankfully I’m at the point of my life where I’m, I’m able to do now the things that I’m passionate about and what I want to do and working on a variety of projects now, including another book and so on and so forth. So, life’s been a great journey for me, and I still have miles and miles to travel before I’m done.

Wow. That sounds like an amazing adventure. I wanted to hit on a few more of the, hit a few of those topics later on. I’d like to start with the Charles McGraw: Biography of a Film Noir Tough Guy. And I picked him up, not in Film Noir, but in The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1954) and came, came in through it to another way. But I’ve always loved his gruff and gravel style of acting. And I assume that’s why you were drawn to that character.

Yeah, I always liked him. He was always distinctive, that jaw and the voice. In fact, his daughter told me at one point that she said, you know, you’re frightening my friends. This is when she was a young girl would that voice. And he said, you know, if it wasn’t for the voice, we wouldn’t be living here in a nice house on the Hill, in studio city with a swimming pool. So, don’t complain about my voice. But yeah, I always liked McGraw. I remember going to see Spartacus when I was a young kid. And being disappointed when Kirk Douglas drowned him in what looked to be a bad of chunky beef soup in the first the first quarter or first third of the picture. And I was disappointed he had such a, such an abrupt exit. But I always I always looked for him and so forth.

And this was when I was still living in San Diego and as I did some, you know, just some pretty superficial research on him, I found out that his death was very mysterious and not mysterious but tragic and kind of ambiguous. He apparently had fallen in a shower and cut his arm and bled to death in 1980. And there wasn’t a lot of detail about this. So, on my own I just started doing research about him and so forth. And in those days. And I say in those days, this wasn’t, this was what you know, maybe 20 years ago or something like that, but you, you had a lot of information cause the internet was coming into full flower and there was a lot of information that now either due to privacy laws you can’t get hold of or they want you to pay for it or so forth.

But in those days, there was a lot of access to stuff. And I found out that the house that he passed away in the mortgage hadn’t changed hands since the 1950s. So, I deduced, well the same person that owned that house when he passed away was still living there. Then I got a copy of his death certificate from the LA coroner’s office, which I understand you can’t do anymore unless you’re a member of the immediate family. And when I got a copy of the death certificate, it was signed by the, the police department. And it was also signed by a woman who was not his wife as a witness. So, I thought this was, was kind of curious and her name was Mildred Black. So, I figured out she was the one that owned the house that he passed away in and still own the house.

So, what I did was I wrote her a letter saying, Hey, I’m doing research on Charles McGraw. And I might’ve said I was writing a book, although that really hadn’t taking full, I hadn’t really figured that all out yet. And so, I wrote her a letter and I never got a response. So fast forward to, let’s see, 1999, I think 2000 around that time, this was when the American Cinema Tech started the what they called the “Annual Festival of Film Noir,” which is now Noir City Hollywood that I co-host and co-program with Eddie Muller. And I went up from San Diego to see that. And I drove by McGraw, this house in studio city and it looked like it was like an old-fashioned bungalow in a, in a nice neighborhood. But you could tell this was a house that had been lived in and it was really late.

And I didn’t want to just go ringing the doorbell and show up at somebody’s house at like nine o’clock at night. So the next time I came up I came up with a friend of mine and I went to the house during the day and there was some guys working in the yard. So, I said, “Hey, is Ms. Black there?” And he says, sure. And he is Millie and this nice older lady with a sun visor and shorts comes out. She said, what can I do for you? And I said, yes, my name is Alan Rode. And I wrote you a letter. And she reached out and grabbed my arm and said, you must be the one that wrote me about Charlie. I’ve been waiting. I’ve been hoping you’d show up. Please come in. And so that was when Mildred Black and the whole Charles McGraw thing opened up for me.

And to make a long story short, I became really close to Mildred. In fact, my wife and I were both, became very close to her and my wife actually became one of her caregivers as she passed away just before the book was published. But I absorbed much more about McGraw’s life. I met his daughter. I met a lot, a number of people who still knew him, who were still around. One guy in particular was a fellow named Bobby Hoy. HOY who was a stuntman, actor, who I became very close friends with was just a lovely guy. And Bobby was in shows like “The High Chaparral” and stunt doubles and a lot of TV shows and he was, he was like Charlie McGraw’s little brother. And so, as I learned more, more and hung out with these people, scrapbooks and photographs, and I went out to Millie’s garage one time to help her clean up.

And there was a, it’s like a wardrobe thing out there and this was where all McGraw’s stuff was there that he had left. Because he had left his wife at some point and had moved in with her. And so, I looked, and I found all of these 16 millimeter films, home movies, that he, his wife and he had shot in the 1950s. And so, I found these movies and I went ahead, and I had a 16 millimeter projector and I projected this on the wall. At that time, we were living in an apartment in Encino and there’s this guy striding across a road somewhere at a film location back East. It was very green and everything. And I’m looking at this and I’m going, I know that guy. Who is that? And then it moved to where there were shots of Alan Ladd.

And what I figured out it was, it was the movie, The Man in the Net (1959) made and shot in Connecticut in 1959. And the guy striding across the road, waving his hands and talking to all these functionaries that were following around was Michael Curtiz. So, I had this, I had this early intersection with Michael Curtiz and then I saw all these home movies with McGraw and so forth. And then she even gave me, he had his old raincoat that he wore in the movies, like The Killers (1946) that I still have and all those. So, at some point I decided, you know, I really need to write down this story about not only McGraw, but the whole milieu. The way Studio City was in the 1950s with all the TV shows that were mostly all westerns and this whole group of stunt people and actors that hung out at the taverns and so on and so forth.

And you’re a, it is completely gone. I mean if you go to Studio City now, it’s, it’s a, you know, it’s Southern California strip malls and this, that and the other thing. And back then it was a little town and you knew who the guy was that worked at the 76 station and who drank with the bookies and the bar down the street. And I ended up knowing, getting to know Dick Martin of “Rowan and Martin [Laugh-In].” It showed up in one of the home movies because he was a pal of McGraw. Because at that time he was a bartender and McGraw. I knew a lot of bartenders. So, all of this kind of all kind of took off. And I always refer to the McGraw book as a moment in serendipity that just kept going on. And it turned into a book and the, and the book was very well received, and it’s still well received. I still get the occasional email or comment from someone. I still, I still get a check twice a year. So, royalties. But it’s nice. That’s a great book. Yeah, that’s an amazing story. I just to get in there and actually just meet all those people.

I heard another story, another author, and that was kind of the same thing, but that’s not going to happen in 10 years. Most of the, most of the people, most of the people that most of the people that I met and talked to about McGraw, they’re all gone back. The people that I talked to about Michael Curtiz they’re almost all gone. And if I tried to write that book now and that book took me like five, six years to write. But if I tried to write that now I wouldn’t be able to talk to Stu Whitman. I wouldn’t be able to talk to Gene Reynolds. Yeah. I mean Curtiz died in 1962 so what was, how many years ago was that? Over 50 years ago. And most of the people that worked or knew these folks are gone.

And so, it would have been a vastly, both of the books that I’ve written would have been vastly different. If I tried to write it nowadays. And I think you can see that I think a lot of the contemporary writing about films and blogging and so forth I think there’s a lot of usefulness to that. And all, all writing and all like blogging and all this stuff, it’s not all creativity created equal. There’s a lot of there’s a lot of good stuff out there, but there’s a lot of stuff. It is merely taken from books that has been repeated down through the years. Right. And one of the things that I found out as a writer is that there’s no substitute for primary source research. And particularly in writing about Michael Curtiz‘s where most of the information about him was secondhand antidotes and stories that have been passed down for years.

That, that and a lot of them, the veracity of some of this stuff really wasn’t there at all. And I think it’s the biographer or the historian or the writer’s point of view from a nonfiction perspective is that facts matter and what, what really happened mattered. And I’ve always tried to bring that out in my writing rather than just going and reprinting some antidote supposedly from the set of Captain Blood (1935). It has no attribution for any of the quotations attributed to the principals and stuff like that. It’s almost like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) when the rumor becomes the truth. That’s exactly print the legend and Curtiz became Curtiz in particular became the I referred to him in the prologue of my biography is the anecdotal gift that keeps giving because there’s always Michael Curtiz stories. And I was doing, I was hosting a screening UCLA generously let me program three months of Curtiz films at the Billy Wilder Theater in Westwood.

And I was going up to introduce a triple bill and the place was sold out and I had sold a bunch of books and very excited and a very well-known director buttonholed me and said, I got to tell you this story about Michael Curtiz and I didn’t want to be rude, but I needed to start the show. So, I’m kind of like letting this guy, and this guy starts telling me this shopworn story about Curtiz being serviced by some ingenue behind the flats on some set. The story varies. These are, it was Casablanca (1942), or another picture and so forth. And I think every person I interviewed, every male that is, you know, lean forward at some point said, Hey, have you heard this story of Curtiz? And you heard this? So, I had heard this story and this, this director is telling me this story and all good faith.

And he looks at my face and he says, you’ve heard this before, haven’t you? And I go, yeah, about 150 times. But that’s okay. And so when I went up to introduce the picture, I said, Hey, I’m sorry for being late, but I was being told a story about Mike Curtiz and approves one thing, even though he’s been dead for more than 50 years, he remains the antidotal gift that keeps on giving. And, and so but I found out a lot of the things that were said about him particularly from a professional point of view that everyone hated him that he was mean to everybody and sadistic. And he was a hack director who just shot the script. And I found that many of those things were absolutely not true at all. So, it always, it always gives me pleasure to set the record straight on, on things that have been accepted as fact. But I always find the factual side of the story much more interesting.

Right. Good scholarship. And the name of that book is Michael Curtiz a Life in Film.

Michael Curtiz a Life in Film from the University of Kentucky Press. And I’m pleased to note that the UK press is bringing it out in paperback next year in February. And I’ve written a new afterword to it because one of the things I’ve discovered is when you write about something or some person after you do it, then all of a sudden you become privy to more information. You know, like the people that came up to me and said, oh, we rented a house from Curtiz his brother, and we have all these photographs. If only we had known you were doing this and you know, and, and since that time I’ve met Curtiz’s grandnieces from his one of his sisters in this is their, their grandmother was Curtiz’s sister in Hungary. And I found out quite a bit about what happened to Curtiz, his family during World War II. And what happened with a number of these children did he had out of wedlock, I think he had four children out of wedlock by four different women during the 1920s and into the 1950s. And I found out quite a bit more about this, that that is that I put in this put in this afterward. So, it’s very gratifying that the book has been successful and it’s, it’s gratifying that it will be out in paperback the next year.

Looking forward to that. Let me just though, just a basic question now. He’s done so many films. What do you think is Curtiz best film?

Oh, I can’t really answer that. That’s like asking who are your grandkids, you liked her best? Yeah, it’s, it’s a there’s, I mean, one of the points I made about Curtiz is that he was relatively unknown and unappreciated except for writing about him in the context of, excuse me, of, of his broken English and his personality foibles and you know all of his, his I mean, David Niven used “Bring on the Empty Horses,” which was a Curtiz directive from a Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) that Niven was in with Errol Flynn can use that for the title of his bestselling memoir in 1985. But his films we celebrate Yuletide every year with White Christmas. We celebrate Independent the 4th of July for the Yankee Doodle Dandy, and we fall in love every time we see Casablanca (1942).

Yet his work has been venerated for many years and through generations, yet no one really venerated him as a filmmaker which I thought was, was very unjust, particularly when you look at the breadth and depth of his work. Also, I don’t, I think he was, went unappreciated because he didn’t fit into the, a round peg, round hole theorem of the auteur’s theory. It really started getting espoused in the late 1950s into the early 1960s. And he also didn’t he wasn’t around to get interviewed by Richard Schickel and like Raul Walsh spinning all his stories in front of a rap group of film students about stealing John Barrymore’s body and putting it in Errol Flynn’s house and Hitchcock and all this other stuff. So, he, a lot of, a lot of things in life have to do with timing.

And because he died in 1962, he, he wasn’t around to be appreciated. And he was also a very he liked the public limelight only to publicize his movies and publicize himself so people would see his movies. But because of his all of these kids that he had out of wedlock and everything, nobody really knew about any of this stuff and he didn’t want anybody to know about his life and times and so forth. So, he kept personally, he kept a low profile and he wanted people to, you know, write about his movie sets that had a sign that said Curtiz spoken here and all this other stuff. And he wanted people to talk about him only in relation to his movies, not as personal life.

I see. I was getting to make sure I’m understanding this right. He made some of the greatest films ever, easily. Oh, the ones you’ve named you know, The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), The Break Point (1950). But he took whatever, like Little Big Shot (1935) and The Comancheros (1961). And is that are you saying that like, because he, he did such a diverse type of movies that he was never appreciated?

Yeah, I think, I think that’s, I think that’s part of it. He was addicted to making movies. And in the days, you know, he made, he ran a movie studio and was making movies as kind of a Hungarian version of David Selznick or somebody like that in the teens before and during World War I. So, when he came to America, he was the guy that had made over 70 feature films and he came to Warner Brothers in 1926 and he worked at Warner Brothers until 1953. So first off, he more than any other American director and he became a quintessential American director. He determined the brand at Warner Brothers, the type of pictures that they make and the style and so on and so forth. And the other thing is, is that he did, back in those days, in the twenties and the thirties contract directors were contract directors.

The studios, the studio bosses ran it. They were making movies as product for the most part to put it in their theater chains particularly Warner Brothers that had acquired a vast number of theaters. So in like the, I think the mid-thirties, he was making six movies a year. Yeah. You know, so he, he did what he was told, but as he became more successful, and particularly in the late thirties when he really hit the big time first with Captain Blood (1935), [Charge of the] Light Brigade (1936), Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), Four Daughters (1938) and he started getting nominated with Academy Awards as he moves into the forties, he did have more authority to, you know, with the exception of the stars, he would, he would have his favorite character actors. He would populate the film cast it. He rewrote, he, he added scenes. He rewrote scripts. And this was kind of the interesting thing to find out his relationship particularly with Hal Wallis and Jack Warner. Curtiz was always trying to make movies.

He considered his, but it was, they, it was really their movies and he thought they were his. So there was this constant, particularly in the early thirties, as a Wallis’ star rose. And he became the uber producer at Warner Brothers and had this incredible run of success. And Curtiz was they’re making Wallis’ most important pictures. And Wallis was trying to bend him to his will and Curtiz was not bendable. He would say, I’ll shoot the script, I’ll do whatever you say. And then he’d go down to the set and do whatever he wanted or location. And the vituperative memos from Wallis that I reprinted quoted from them copiously in my book. He finally, and, and the, the ironic thing was he and Wallace became very close friends, very close friends. And Wallace always resented the fact that, when towards the end of Wallis life in the seventies, as his career wound down, and he was being interviewed at, you know, AFI seminars and so on and so forth, that everyone was talking about Hitchcock and Wellman and, Billy Wilder.

And he said, what do you mean? Curtiz is a great director. He belongs with all of them. So, they’re, they’re legacies. The two of them, how Wallis and Curtiz’s legacies were intricately tied together and Wallace always went out of his way to make sure that Curtiz got his due or try to. But Curtiz was very much his own man and he finally had to accept a certain amount of supervision and a certain amount of control under Wallis and Warner. But he also, as his pictures continued to make money, he became really the cash cow at Warner Brothers. So, he had an increasingly amount of authority and he ended up getting his own production company at Warner Brothers, I believe in 47 which I chronicle in my book, which was definitely his due. But the timing, again, timing is everything.

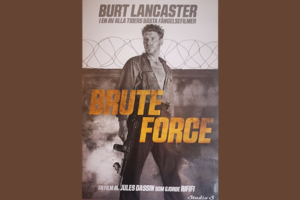

The postwar box office swoon, the advent of television, and the antitrust suit from the government against the big five studios, forcing them to divest their theater chains. It was not a good time for Curtiz to start a movie production company and add to it that he was working with Jack Warner who never I think Jack Warner could squeeze a nickel hard enough to make the Buffalo peel. And, and Jack Warner pioneered the term of creative accounting that really gained full flower in Hollywood and still goes on after World War II because the whole studio system changed. And it went from you know, a studio that was cranking out like an assembly line movie after movie after movie to keep people in the theaters to more of a smorgasbord of hiring independent producers and partnering with, with Burt Lancaster and Alfred Hitchcock so on and so forth and putting out much fewer pictures because the costs for everything after the war really exploded. So any rate, but, but Curtiz he was a great filmmaker and, and had great instincts about everything having to do with film because film was his life and he was content to subordinate himself ultimately to the Jack Warners’ and the Hal Wallis’ and the Darryl Zanuck’s as long as he was allowed to continue to make movies and movies came before fatherhood came before being a husband came before even came before sex, which was a close second.

I guess that’s the way it was back then. Yes, it was. Yes, it was. I have a question I want to ask you and I’ll cut this out if it doesn’t make any sense and I’m a little embarrassed. I read an article that you wrote about blacklisting and the union takeover. I mean the mafia takeover. Yeah. And I cannot find it again. Well, can I ask you a question that, to speak about that even though,

Yeah, you can ask me anything you want.

Well, yeah. The article, which has to do with the Film Noir Foundation. The article and is that the article and the Noir City magazine about the Chicago Way? About how the gangsters took over the IATSE in the thirties and started shaking them. Yeah, yeah, yeah, sure.

Okay, good. Could you tell us a little bit about your article, the own the Chicago Way, the blacklisting and the mob involvement?

Sure. Well, well that, that’s an interesting piece of history and it has been written about by other people. It’s a guy named Gus Russo wrote a very interesting book called Supermob [: How Sidney Korshak and His Criminal Associates Became America’s Hidden Power Brokers] about the Chicago outfit and its tentacles that extended into that extended into Hollywood and how much influence for many years the mobsters had in Hollywood. And so and, and in particular there was a guy that lived in Hollywood for many years named Sidney Korshack who was one of these guys that all he had to do is pick up a phone and make a phone call and union problems ceased. And how the, how the mob got into Hollywood. Well, first off, Los Angeles had had during the twenties and the thirties was, it was a totally corrupt town. The mayor Frank Shaw was removed for a due to a special election for malfeasance in office. I think it was after one of the people running against him had his house blown up by the police lieutenant with the LAPD. I mean it was, it was really wide open. And so, what happened is these two guys from Chicago and I’m, I’m having a senior moment here with names. Let’s see if I can find this article here. Bear with me and I can, I can call it up. So you must be a contributor to the Film Noir Foundation.

I am and I want to talk about that very important work and a little bit. I really was just amazed by Trapped (1949) after I saw that.

Oh, you saw the new DVD? Yeah, that was, that was, that was a lot of fun. Article on Raymond Burr. Any rate. So any rate the, the, the mob got a hold of the IATSE there were a couple, there are a couple of crooks that started in Chicago, started shaking down the Paramount Theater chain run by Barney Balaban. And these, these guys were, were kind of small timers. One of them was an alcoholic, a union official for the International Association of Theatrical Workers and Stagehands, which is the, the shorthand version for that union is the IA and these guys started getting money. They went around town and bragged about it and they bragged about it in a, in a bar that was controlled by Al Capone’s cousin. So, he listened in and then these two guys were frog marched into the eerie of the head of the outfit at that time.

And basically organized crime went ahead and when the IAPSE had their international convention, they sent all these gunmen and people like Meyer Lansky and ‘Dutch’ Schultz all these people and basically put their, put their own creatures and in charge of the union. And so, when these guys came to Hollywood, they took over the locals and everything and they started shaking down the studios for labor peace. And the studios, when this whole thing unraveled people like Harry Warner and L. B. Mayer portrayed themselves as victims. But really what they were doing was buying labor peace because if they paid off the gangsters and you know, delivering them suitcases of hundreds of thousands of dollars, they didn’t have to pay their employees nearly as much money. So, they were really buying labor peace and saving money. And inevitably the whole thing became unraveled.

The two front man ended up going to jail and then one of them got angry and rolled over, testified against, you know, the boys in the back room, so to speak, in Chicago. And they were all convicted and went to federal prison in 1940s, in the late forties’ early forties, I think. 43 around that time, including, you know, Johnny Roselli and ‘Cherry Nose’ [GioeCharles], [??] Scott, you know, all these Italian gangsters with nicknames and they all went to prison. And as it turned, they all got out early due to a lot of circumstantial evidence that the attorney general and President Truman were imposed upon or bribed to let them go. And Truman, by the way, despite his stellar historical reputation of the buck stops here and everything, President Truman was a product of the corrupt Pendergast machine, right in Kansas City, Missouri.

And used to be a bag man and would pick up money in whorehouses and shake down money and so forth. And he was I believe he was reached out to and made an accommodation in this case while he was while he was president. So, it’s a really interesting story on how the gangsters got control of the key union in Hollywood and it’s called the Payola Scandal. And it it’s a piece of history because when these people went to jail the union was taken over by anti-red, very reactionary elements. And this is when the, the red baiting started, and people had to be cleared in order to work at the studios. And so forth. And a lot of this red baiting I discovered started when the gangsters, we’re in control of the unions.

And when liberals started pointing out that they were ripping off the membership and using strong arm tactics they accused their critics of being reds and being disloyal and so on and so forth. And you see the same tactics have permeated the body politic going into the fifties with the blacklist and so on and so forth. So, it’s an interesting certitudes route of how gangsters ended up really fomenting a lot of the blacklist stuff are certainly laying the groundwork for it during the twenties and thirties in Hollywood. And then it became after World War II and in the 1950s, the blacklist really permeated the entertainment field. Right. And so forth. So, it’s an interesting, it was an interesting article.

So really a different version of history. You know, then we’re normally taught.

Well that, that’s true. And there’s a lot of ’em. There’s a lot of history out there that has either gone under-reported or perhaps the conclusions that I draw from it are a little different. But I always, I always try to draw conclusions based on facts and what happened, what happened to what happened to the unions and how the gangsters got control of the union and how they shaking down the studio bosses who you know, the studio bosses, Harry Warner was buying them vacation tickets and that to go to Europe and to go to all these different places. So, there was a, there was certainly a willingness on the part of the studio heads to acquiesce and wink at this thing because paying off the gangsters was saving them money.

Right. The money wasn’t coming out of their pockets.

No. And, and these guys, the, the studio bosses they really cared about making movies. They weren’t lawyers and three-piece suits from Ivy league college. They grew up looking at Excel spreadsheets figuring out you know, focus groups and testing everything the way it is now. They went with their gut and they risked all. But they were these type of people that came up with their boots, bootstraps, you know, Sam Goldman was a glove salesman. Louis B. Mayer sold junk. Harry Cohn was a, was a really, really tough guy. And these guys grew up through poverty and their attitude was, I did it. Everyone else can do it the same way. I, I don’t, I don’t believe in unions. Why should I have to do this? I treat people how I want to treat him. And if they don’t want to work for me, then it’s tough. And, and certainly this is a real philistine type attitude to take. But that was how it was. That’s how these guys were. And when anybody wonders why the movie industry and Hollywood is so permeated with unions for everything, all you need to do is go back and look at history. And it was because of the way that the employees were exploited and treated that we, we ended up with all these unions here. So, for every action there’s a reaction.

Okay. All right. I want to jump back to you mentioned the 2020 Arthur Lyon’s Film Noir Festival. That’s correct. And could you discuss the legacy of that a little bit and re-mentioned, and you mentioned the rescheduling of it.

Sure. Arthur Lyons was a friend of mine. Arthur was a writer who came up with a very unusual protagonist and his detective mystery novels named Jacob Asch, and he was a Jewish, like a Jewish Phillip Marlow and in contemporary times. This is back in the seventies and eighties when Arthur wrote these books. And Arthur was a really, really top writer and he would have writer’s conferences in Palm Springs, and he had Mickey Spillane and a lot of detective fiction novels. And of course, this bled into Film Noir. So, he started the “Palm Springs Film Noir Festival” back in 2000. And I got involved with Arthur, I believe 2002. We became friends. I started helping him with guests. I started doing some of the interviews with people like Mala Powers and other, the old timers that Mark would, that Arthur would invite.

Jane Russell, I mean, we would have people like Tony Curtis, Jane Russell, Mala Powers, Kevin McCarthy, and I got to know Mickey Spillane because he was a friend of Art’s and he’d be there every year. So, it grew from a very small festival and art would show like VHS tapes and anything that was, you know, he could cut corners on the budget because he didn’t have a lot of money. And in fact, Arthur wrote a book called Death on the Cheap about the loss world of B-Noir. That’s, that’s a really good book. That is still in print by the way. Okay. And, so any rate, I became friends with Arthur was helping him with the festival and then Arthur passed away unexpectedly in 2008. And the Supple family who owned the Camelot Theaters asked me to take over production of the festival.

And so, since 2008, I’ve been the producer and the host, and I’ve gotten the guests there and program the films. And I have people like Eddie Muller and Foster Hersch join me and I’ve had all kinds of celebrities, writers, different people there from Ann Jeffries, Ernest Borgnine, Marsha Hunt, Norman Lloyd. I’ve had Norman there twice. Who’s like the living oracle of old Hollywood. He’s going to be 105 this year. 106. It’s incredible. Yeah, you have lunch with Norman and he can talk about working with Orson Wells on stage when Orson was in his twenties and working with Charlie Chaplin and being Hitchcock’s the associate producer and producer of the “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” show. It, it’s just phenomenal. He’s phenomenal. He’s still all there. And so, I had, I’ve had people like that, and I’d been showing more contemporary movies like Miller’s Crossing (1990).

I had John Palito there who was just fantastic and all kinds of people. So, the festival through the years has grown to become really an international event, very well attended and really fabulous. So this year I usually have it the second week of May to coincide with Mother’s Day and we had mother’s day on Sunday and show something appropriate like Boris Karloff digging the cadavers in The Body Snatcher (1945) on Mother’s Day and I had a Boris’ daughter Sarah there and we had a great time and she brought in home movies from her childhood and her father’s last interview and really delightful. So, I’ve rescheduled the festival with the Palm Springs Cultural Center and we’re going to put the festival on in Palm Springs on December 3rd through the 6th. And you know, I’m hoping fingers crossed that life will return to some sense of normalcy by that time and people can for gather to some extent and movie theaters and I can produce and put on the best festival that I can put on in December of this year.

So, we’ll, we’ll wait and see what happens. I’m looking forward, I’m going to try and get out there. Great. That’s super, super. I guess a herd is just a little news store that is a virus may bring the drive-in theater back. I thought it was interesting people sitting in their own cars watching movies. Oh yeah. Yeah. In fact, I’m, I’m working with the one of the other things I do is I’m the chairman of the theater committee for the American Legion post in Hollywood the Legion Theater, which is a gorgeous, restored $4 million restoration theater. And we’re looking at maybe doing a drive-in the parking lot there and it’s right on Highland before the Bowl. It hasn’t reached, hasn’t, you know, it’s a work in progress. It’s still being discussed, but we’re working on that. In fact, the last show that I hosted, second to the last show, we had to cut Noir City Hollywood short.

And I hosted a, I think this was on March 11th hosted a veteran and Noir night there and showed a couple of veteran-themed war movies, post-World War II movies and had Victoria Mature, Victor Mature’s daughter there. And everyone was dressed up in forties regalia. And I had, you know, 300 people there. And it was a great show. And the Legion Theater is really a beautiful venue. We showed we partnered with a retro format and showed a new print of Chaplain’s, The Gold Rush (1925). And the theater holds, I think 482 and it was completely sold out, piano accompaniment and so forth. So, there’s really some exciting things happening at the Hollywood Legion Theater that I’m involved in as well. And it’s, it’s also a way, the Legion is not the, my grandfather’s legion during the 1950s and the forties. It’s a very proactive in helping veterans and supporting the community. And as a veteran, I look at this as a way of this point in my life, giving back a little bit. Well, doing the stuff with the Legion Theater. So, I’m enjoying it. There’s some super people there, so it’s a, that’s another thing that I’m doing too. Keep me, keep me off the streets and keep me active.

That’s a very awesome. You said in, I believe in your biography on your site that you thought that you’d rather you’d enjoy watching a 75-minute B that was tightly made. And out of that, I want to ask, why do you think a study or the watching of Film Noir it’s worth it, or why is it important? Why is this,

You know, important? Important is like beauty. It’s in the eye of the beholder. However, I do think that as time moves on and people have less of a sense of the post-World War II era and what happened during the war and how people talk and how they dress. Now certainly Film Noir movies are not like a documentary of some kind, but I think you do get a sense from watching these movies of what life certainly was like from a popular culture point of view and how people dressed and how people acted and so on and so forth. And I think it does give you a sense of where the country was. I mean, after World War II from an entertainment perspective, remember during the war, people were watching Andy Hardy movies and they were watching John Hall and Maria Montez and Turhan Bay dressed up as you know, saving Baghdad from the Mongols and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and the Sherlock Holmes and the Universal horror movies and so forth.

But after World War II, the country really changed from a cultural perspective. Millions of people had been involved in the war to some extent. Many of them had seen or experienced or perform terrible things that they wouldn’t have considered. Women were involved in the war or they were home working. And the role of women had changed, and society had changed considerably. So, I think after World War II in addition to the pop culture, I think Hollywood and the movies kind of grew up. They left adolescents, they left Andy Hardy hitting up Louis Stone for a 10 spot to pay for dinner and those types of things. And more of an adult entertainment and more what I would call post-war Film Noir realism, which is kind of a clunky term, but it’s the best I can come up with right now.

Came to take over and people wanted more reality in their entertainment. And I think you see that in the film, the postwar Film Noir, the phenomenon, it ended up as the fifties went on, it kind of morphed into television. And then you started seeing shows like “China Smith” and “Dragnet” and “Perry Mason.” It had dark crime, pinged themes and so forth. And, and, and as this society changed once again with the baby boomer generation and Technicolor and widescreen and 3-D and all of these other things. But I think Film Noir also gives you a sense of a tight storytelling and story writing where, you know, if you want it to indicate as a plot point that these two adults were having a sexual relationship outside of marriage or outside of their marriages that it couldn’t be just out in the open with two of them jumping into bed.

It had to be suggested because the censorship of the production control authorities of the Motion Picture Association of America they were still married to a censorship code that they had created and chain themselves to in the early 1930s because of the protests by the Legion of Decency and these other organizations complaining about the debauching effects of movies and so on and so forth. So the movie makers had to satisfy the desire to tell more adult stories while still adhering to this code of conduct. It became more and more absurd as time went on where you had a married couple, but they couldn’t set on the same bed together and have a conversation and so forth. So I think the creativity of having to you know, work with the production code while telling stories to a country and a world that had changed significantly makes for some very, very interesting entertainment experiences and popular culture enlightenment.

It continues during this day. And I think Film Noir is a I don’t think it’s a genre particularly, I think it’s more of a style. And or a movement. And this is something where I think someone nowadays who’s known and is content to watch movies off of cell phones and get their entertainment elsewhere, I think they can still identify with tightly wound stories that identify with the human condition of larceny and lust and greed and doing something. Even though you think you know it’s wrong, you go ahead, and you do it anyway. I think some of the themes of those movies are rather timeless. And I think one reason there’s been a Renaissance of interest in classic film is due largely to Film Noir. I think it, I think it strikes a vibe in the human soul that, that people respond to.

Okay. Well, as we’re getting closer to the end here, I wanted to ask you about the Film Noir Foundation your restoration work and the need for support.

Well, the film, the Film Noir Foundation was, was founded by Eddie Muller, who’s the president and you know, Eddie now has the Noir Alley show on Turner Classic Movies on the weekends. And this Film Noir Foundation really started around Eddie’s kitchen table when we found we couldn’t find the movies for the Noir City Festival in San Francisco. And the studios didn’t have prints of movies that we had seen on TV for years. And as it turned out, a lot of these movies had fallen between the cracks. Prints were not available and so on and so forth. And now with, with film being overtaken by digital DCP’s, Blu-rays and so forth, there’s still a lot of films that have not been, not been digitally preserved and so forth. So what the Film Noir Foundation, you know, our mandate is to rescue America’s Noir heritage and we’re really a grassroots organization because after the bills get paid, we raise money with our festivals that are now in seven different cities.

And with our merchandise, t-shirts, cups, books, our online magazine that we put into an annual every year. And that money goes to restoring and preserving films. And we have a, well, you know, without trying to brag here, I think we have an amazing track record. If you look at the Film Noir Foundation website, we have preserved a number of films that otherwise would be lost, and these are full restorations. And we’ve also had funded the striking of prints of many films that the studios owned but didn’t have prints available. And you know, of course you have to wrap your brain around the Film Noir Foundation funding a major studio print so they can now charge us money to show their prints. You know, that, that that takes a, that certainly you have to swallow hard a couple of times to do that.

But we, we’ve, we’ve formed partnerships with the studios. They’ve been very supportive of our work and we’ve now been able to bring several of the films that we have preserved. We’ve now brought them out on Blu-ray and DVD. Because let’s face it, not every city has a Noir City Festival that shows up every year. Right. So, we’ve been able to make these films we’ve preserved, such, as you mentioned, Trapped (1949) earlier, Woman on the Run (1950), Too Late for Tears (1949), The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950). We brought these out with our partners at Flicker Alley that do a super job. And we’ve also managed to bring these out with you know, what I would call for lack of a better term, the criterion treatment where a booklet is written and we have a special featurette about the making of the movie and the history behind it, or a featurette about the filmmaker.

In the case of our latest released on Trapped (1949), we did a documentary on Richard Flesher with Mark Flesher, his son who was just a wonderful raconteur and a filmmaker and a producer in his own right discussing his father. And I’ve been able to contribute some of the commentary tracks for some of these films. So, it’s been, it’s been a great ride and we’re working on several projects on which we speak and you know, all people have to do to contribute is go to http://www.FilmNoirFoundation.org send us 20 bucks. And you will start getting the Film Noir-Noir City magazine that has some of the best contemporary writing on Film Noir, both the past and the present and that’s delivered via PDF in an email. And then there’s levels of contributions. But we’re really a grassroots organization and we’ve gotten our money from people who believe in what we’re doing and who like watching a classic Film Noir / Film Noir movies and like reading our material and stuff.

So I encourage all of your listeners to go to a, the Film Noir Foundation website, see what we have to offer and send the money in because the money does go to directly to preserving film and the people who buy the tickets to our film festivals and buy our gear and everything. Trust me, Eddie Muller and I are not being personally enriched by any of this. It’s going to preserve the films. And so, it’s a, it’s something that I’ve been associated with for a long time and something I’m very proud of and the work continues and I’ll put the link in the show notes. And I love when my magazine comes in because there’s always some exciting information there. Great. Super, super. I’m glad. I appreciate it. I appreciate your support. Alan, what did I forget to ask you?

Gee, I don’t know McGraw, Curtiz, the Film Noir Foundation. One thing I would say my website, Alan K. Rode Interview ALAN K RODE dot com on my website. I not only have my books available for sale where people can buy them, and I will personalize them and autograph them and send them to them priority mail. But I have some of my writing is there. And I also have the videos of the discussions I’ve had with some of the people I mentioned like Norman Lloyd and Nancy Olson and Marsha Hunt and a lot of these are on the Film Noir Foundation website as well with Eddie Muller‘s conversations with the different people we’ve had as guests at our festivals over the years. So I encourage people to go to not only the Film Noir Foundation website, but to Alan K Rode‘s website. It has, you know, all the DVDs and the blue rays that I’ve done commentaries or produced myself and, and different things. And lot of the videos of the interviews I’ve done over the last 10 years are there. So, I encourage your listeners to check it out.

Okay. Well, Alan, I want to thank you and I’ll put links to that also in the show notes and on the website. So, there is so much good information that you provided today. And I want to thank you again and I know everybody’s going to love it.

Okay, great. Now where can I, where can I find where can I find your website and this this interview and your work? Where is that?

I’m at ClassicMovieRev.com. But I will send you – I will send you a link before it goes live, let you know where their thing, there’ll be a video copy a vocal copy on YouTube as well. All right. Thank you very much. Enjoyed talking to you.

All right. Bye. Bye.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.